A Life's Work

Fr. Viktor's Monasteries

-

First Monastery: the Schloss Gatterburg in Munich, Germany

In 1923, Frs. Viktor and Valentine established their first monastery in the Schloss Gatterburg, a neoclassical mansion in the Pasing district of Munich. See a larger photo »

-

Schloss Gatterburg, Munich

Originally built in 1869, the Schloss Gatterburg was the home of the von Gatterburg family. Countess Pauline von Gatterburg continued to live in the mansion until her death in October 1931. See a larger photo »

-

The Second Monastery: Maria Schutz, Austria

This is the Marian shrine of Maria Schutz in Austria. The Passionists acquired it in 1925 with the asssitance of Vienna Archbishop Friedrich Gustav Cardinal Piffl. See a larger photo »

-

The Shrine of Maria Schutz

The shrine of Maria Schutz owes its very existence to instances of miraculous healing. In 1679, people suffering from the plague drew water from a well that was near a statue of the Virgin Mary. They were mysteriously healed by its water. The shrine was built later in 1722. It continues to be one of Austria's most popular pilgrimage sites. See a larger photo »

-

Inside Maria Schutz, Austria

The altar of the shrine of Maria Schutz. See a larger photo »

-

Snow in the Austrian Alps

Fr. Viktor sent this photo to his relatives in Sharon, PA. Even to people accustomed to the rigors of a Pennsylvania winter, this would have been an impressive sight! See a larger photo »

-

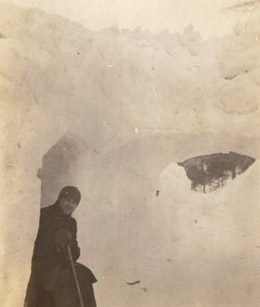

Digging Out

A Passionist digs tunnels in the snow outside the shrine of Maria Schutz. See a larger photo »

-

Maria Schutz, Austria

A view of the parish church taken from the parsonage in Maria Schutz, Austria. See a larger photo »

-

Maria Schutz, Austria

This fantastically ornate house nestled in snow is the parsonage at Maria Schutz. See a larger photo »

-

1937: Grim Portents

The Nazis closed the preparatory school that the Passionists opened in the Schloss Gatterburg. Swastika flags visibly hang from the windows. See a larger photo »

-

Third Monastery: Schwarzenfeld, Germany

Schwarzenfeld was one of two candidate sites for the German Passionist Foundation's third monastery. Fr. Viktor was drawn to the the pilgrimage church that soared from the top of a grassy hill. Locals called the hill "the Miesberg" (pronounced MEES-berg), and the church upon its peak the Miesbergkirche (Miesberg church, pronounced MEES-berg-KEHR-shah). See a larger photo »

-

The Miesbergkirche

The Miesbergkirche was a pilgrimage church, a stop for travelers making their way to shrines across Europe. The church had been constructed in 1721—the same year that St. Paul of the Cross founded the Passionist order. See a larger photo »

-

Constructing the Miesbergkloster

The Passionists purchased the Miesbergkirche and construction of the monastery—the Miesbergkloster—began in May 1934. The monastery was designed by an American Passionist architect, Fr. Christopher Berlo, C.P. See a larger photo »

-

Mobilizing a Town

In 1934, Germany was reeling from the aftermath of the Great Depression. Like their fellow Germans, most Schwarzenfelders were unemployed and destitute. Fr. Viktor arrived with $200,000 in U.S. funds—enough to hire every able-bodied laborer in the backwater farm village, plus indigents and tradesmen roaming the Oberpfalz in search of work. See a larger photo »

-

Monitoring Construction

Fr. Viktor observes construction efforts with Dr. Michael Buchberger, the Bishop of Regensburg (center). Buchberger recommended Schwarzenfeld as a possible site for the third Passionist monastery. See a larger photo »

-

The Miesbergkloster, 1935

Construction efforts finished in the summer of 1935. The Passionists ceremoniously occupied the building on September 7, and two days later, they began holding observances and living the rhythms of monastic life. See a larger photo »

-

The Miesberg and Schwarzenfeld

This aerial view shows the hill of the Miesberg in relation to the town. The church and monastery are visible upon its crown. See a larger photo »

-

The Miesberg Church and Monastery

This aerial view shows the church and monastery in Schwarzenfeld. The monastery (Miesbergkloster) is the H-shaped structure protruding from the church (Miesbergkirche). See a larger photo »

-

Nazi Confiscation of the Miesbergkloster, 1941

The Nazis confiscated the Miesbergkloster in April 1941, and kept it in their possession until the Americans arrived in April 1945. It first served as a boardinghouse for children evacuated from air-raid prone cities. Later it sheltered scientists working for the Berlin Technical School's Ion and Electron Institute. (Note that the steeple cross was taken down). See a larger photo »

-

Miesbergkirche Courtyard

A ripple-capped plaster wall circles the Miesberg. The stone-spaced enclosure within its confines is a serene place, perfect for reflection. See a larger photo »

-

Miesbergkirche Altar

Gold and faux marble make up this opulent altar. (Historical note: the door to the flower sacristy where Fr. Viktor took up residence during the war years is visible behind the altar, on the left.) See a larger photo »

-

Gate to the Graveyard

This small, private cemetery is the resting place of Passionists. Fr. Valentin Lenherd, C.P., co-founder of the German-Austrian Foundation, was the first to be laid to rest here. Fr. Viktor was the second. See a larger photo »

-

The Commemorative Plaque

Parishioners of the Miesberg affixed this plaque in April 1995, fifty years after Fr. Viktor saved the town. The plaque reads as follows: "In gratitude to honorary citizen Fr. Viktor Koch C.P., Provincial of the Passionist Order. Through personal engagement and civil courage, he prevented in April 1945 an act of retribution by U.S. troops upon the population of Schwarzenfeld." See a larger photo »

-

Schwarzenfeld Skyline

Four buildings define the skyline of Schwarzenfeld: the rust, triangular cap of the Marienkirche, a Protestant church built in the 1970s; the gray, turnip-shaped turrets of the Schloss; the steeple of the Pfarrkirche (town parish church) beside it; and the Miesbergkirche steeple, the highest point in town. See a larger photo »

-

The Crossway

Between 1945 and 1950, statuary and altars denoting the stations of the cross were erected along the walkway that surrounds the Miesbergkirche. This station is the 11th, the crucifixion. See a larger photo »

-

Gazing Up

The gaze of a crucified Christ—even in marble—is indeed a powerful sight. See a larger photo »

-

The Marian Grotto

This grotto dedicated to the Virgin Mary is another altar one finds on the walkway around the Miesbergkirche. See a larger photo »