May 2005:

The Researchers in Germany

-

Our Hotel

We stayed at the Schloss Schwarzenfeld, a castle that had been renovated and converted into a hotel. See a larger photo »

-

Bavarian Identity

Bavarian pride was palpable, both in the abundance of white-and-blue checked flags, and the number of times in which Peter Bartmann, our guide and friend, exuberantly pointed out things that were "Bayerisch!" See a larger photo »

-

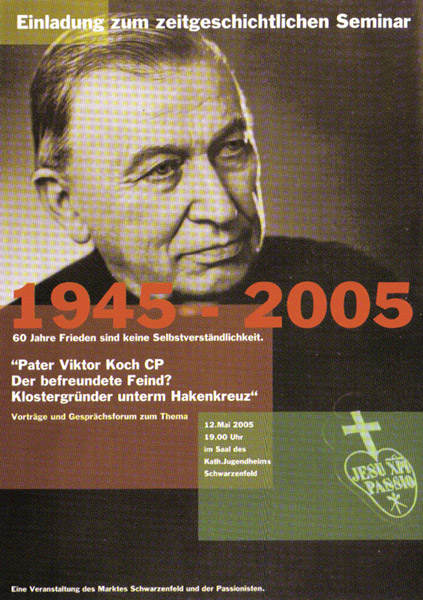

Seminar Poster

The poster announcing the history seminar on May 12, 2005, decked doors on restaurants and street corners throughout town. Katherine was the keynote speaker. See a larger photo »

-

The Wreath-laying Ceremony

After settling in at the Schloss Schwarzenfeld, our guide Peter Bartmann took us to the site most integral to Fr. Viktor's story: the hill of the Miesberg. It was a poignant moment for Fr. Viktor's kin. We even had media coverage. See a larger photo »

-

Taking It All In

We didn't expect this to be such an emotional moment. Until this point, we were researching the past with psychological distance. Touching that headstone made it so real and immediate that we both broke down in tears. See a larger photo »

-

Wreath on the Grave

Fifty years after his death and sixty years after he saved Schwarzenfeld, Fr. Viktor's family visits his grave for the first time. See a larger photo »

-

The Wreath

"From his grateful and admiring friends in America and Germany." See a larger photo »

-

The Flower Sacristy

When the Nazis evicted Fr. Viktor and the Passionists from the Miesbergkloster, he defiantly took up residence in this miniscule church sacristy. In this picture, you see the narrow end of this wedge-shaped room. See a larger photo »

-

The Flower Sacristy

Pictures don't prepare you for the reality of this miniscule room. Ten paces will carry you from one end to the other. Here in this picture, you can see its widest end. See a larger photo »

-

Window in the Sacristy

After the eviction, every day at noon, Fr. Viktor reached through this window to accept his mail. That's all he permitted the Miesbergkloster's new tenants to see of him: a hand. Presumably, he wanted to minimize the amount of information the Nazis had about the monks inhabiting the church. See a larger photo »

-

Fr. Paul's Room

Katherine and Fr. Viktor's succesor, Fr. Gregor Lenzen, C.P., study the upstairs room of the flower sacristy, where Fr. Paul Böhminghaus stayed. See a larger photo »

-

View From the Back Porch of the Miesbergkloster

The Miesberg is a broad, grassy hill northeast of Schwarzenfeld. The church (Miesbergkirche) and monastery (Miesbergkloster) are perched upon its crown. The hill's heights afford a spectacular view of the town. See a larger photo »

-

View of the Town

Red-tiled rooftops spread like a carpet from the foot of the Miesberg. See a larger photo »

-

The Miesbergkirche

A view of the church steeple against a cotton sky. See a larger photo »

-

Sunrays

The colonnaded back porch of the Miesbergkloster. This is one of our favorite photos. See a larger photo »

-

The Plaque

The citizens of Schwarzenfeld affixed this memorial plaque upon the church facade in April 1995, fifty years after Fr. Viktor saved the town. See a larger photo »

-

Close-up of the Plaque

Translation: "In gratitude to honorary citizen Fr. Viktor Koch, C.P., Provincial of the Passionist Order. Through personal engagement and civil courage, he prevented in April 1945 an act of retribution by U.S. troops upon the population of Schwarzenfeld." See a larger photo »

-

A Catholic Town

It doesn't take long to discern that religion is the bedrock of Schwarzenfeld's culture. A life-sized crucifix with a gold-plated figure of Jesus graces the town square. See a larger photo »

-

The Hauptstrasse

This is the Hauptstrasse, or "main street," of Schwarzenfeld. Can you imagine Sherman tanks lumbering along this narrow and sinuous road? See a larger photo »

-

Street View

Schwarzenfeld is a modern town, yet it still exudes a sense of age. The town will celebrate its 1,000-year anniversary in 2015. See a larger photo »

-

Viktor-Koch-Strasse

Schwarzenfeld's veneration of Fr. Viktor didn't end with the declaration of honorary citizenship. When the town opened a new street that would serve as its main thoroughfare, officials named it after him. See a larger photo »

-

The Naab River

The iridescent ribbon of the Naab curls along the eastern border of the town. See a larger photo »

-

St. Nikolaus Apotheke

At the end of the war, a local farmer contracted typhoid from Flossenbürg prisoners who had been hiding in his barn, and the possibility of an epidemic overshadowed Schwarzenfeld. Fr. Viktor coordinated with American military authorities, seeking their assistance in opening an apothecary and distributing medications necessary to combat the disease. That pharmacy was the St. Nikolaus Apotheke. See a larger photo »

-

The Old Rathaus

During Fr. Viktor's day, this beige stucco building served as Schwarzenfeld's town hall. See a larger photo »

-

Frau Barbara Friese

During our stay in Schwarzenfeld, we had the outstanding opportunity to interview townspeople who knew Fr. Viktor. Among them was Frau Barbara Friese, the woman who distributed bread to Flossenbürg prisoners outside the Gindele bakery. See a larger photo »

-

Zita and Karlhans Müeller

Our whole project started with Zita. During a visit to Schwarzenfeld, U.S. World War II veteran Ed Pancoast learned Fr. Viktor's story from her, and then traveled back to the States in hopes of finding the priest's kin. See a larger photo »

-

The Seminar

On May 12, 2005, Schwarzenfelders congregated to the Kath. Jugendheim (Catholic Youth Center) for the history seminar. Katherine delivered a speech about Fr. Viktor's early life and struggles to establish the Passionist German-Austrian Foundation. See a larger photo »

-

Telling Their Stories

After the seminar, a number of Schwarzenfeld's older residents approached us, taking the opportunity to share their memories of the war years and Fr. Viktor's role in saving the town. See a larger photo »

-

Celebrating a Job Well Done

After the seminar, the beer was flowing! From left to right: Gary Koch, Fr. Rob Carbonneau, C.P., Katherine Koch, Peter Bartmann, and German-Austrian Passionist Foundation Provincial, Fr. Gregor Lenzen, C.P. See a larger photo »

-

"It Is Overwhelming."

That was my response when a reporter asked how I felt about my research mission in Schwarzenfeld. (It was also overwhelming to see my name and face in a German newspaper!) See a larger photo »

-

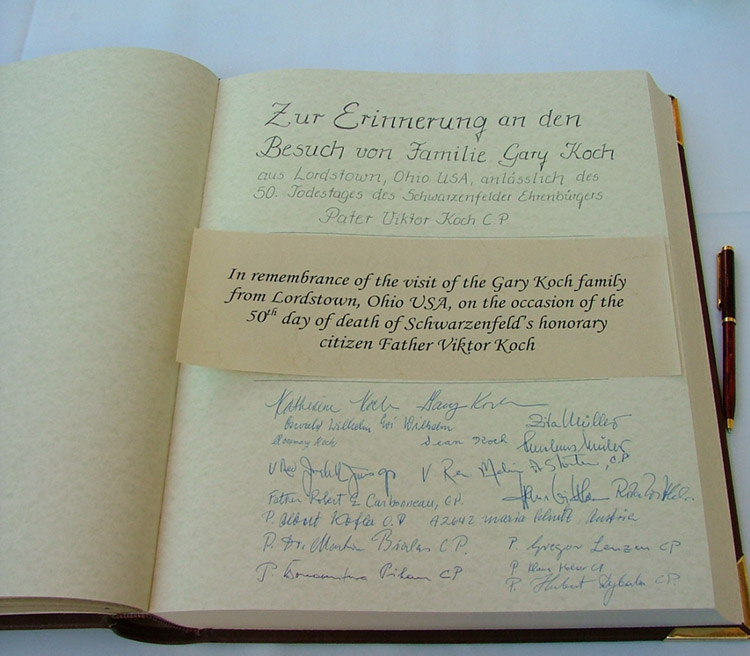

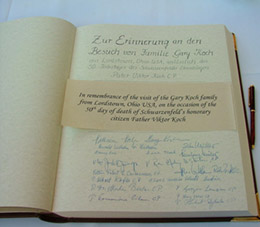

Signing the Goldene Buch

The Germans have a tradition of commemorating events by inviting the participants to sign the Goldene Buch (visitor's book). Here's a shot of the page where the Koch family, the Passionists, and German participants signed their names in Schwarzenfeld's book. See a larger photo »

-

Nikolaus Kainz and His Cousin Christianne

Nikolaus "Klaus" Kainz was a former Hitler Youth from Pfaffenberg, Germany, who witnessed the aftermath of the train station shooting in Schwarzenfeld. The town officials invited him to come during our visit and speak about his experiences. See a larger photo »

-

Katherine Interviews Klaus

Meeting Klaus was a great stroke of luck for Katherine. She has maintained a correspondence with him over the past decade as she wrote her novel. A strikingly honest and objective man, he has been her "check and balance," keeping her research and writing well-grounded in fact. See a larger photo »

-

Sunday Mass at the Miesberg

Fr. Gregor Lenzen, C.P., and the Passionists celebrate Mass at the beautiful hilltop church where Fr. Viktor once preached to his flock. (The door of the flower sacristy is visible behind the altar on the left.) See a larger photo »

-

Courtyard Interviews

After Sunday Mass, Katherine conducted impromptu interviews in the courtyard of the Miesbergkirche. We expected the Germans to be withdrawn and taciturn about their war experiences. Not the Schwarzenfelders. Much to Katherine's amazement, these people wanted to talk! See a larger photo »

-

Memories of Fr. Viktor

Katherine interviews a former altar boy who served with Fr. Viktor. Many thanks to our friend Irmi Ehrenreich (pictured in the center) for translating all of the amazing stories we heard that day. See a larger photo »

-

Milling About

After mass, Gary chats with Fr. Viktor's successor, Fr. Gregor Lenzen, C.P. See a larger photo »

-

Americans in Germany

The Kochs and Fr. Robert Carbonnau, C.P. pose for a photo. Pictured from left to right: Gary Koch, Rosemary Koch, Sean Koch (Gary and Rosemary's son), Fr. Rob, and Katherine Koch (Gary and Rosemary's daughter). See a larger photo »

-

The Researchers and Their Mentor

We met Fr. Robert Carbonneau (center) in 2004 when we visited the Passionist Archives in Union City, NJ. The Passionist historian has been a part of our journey since the beginning. See a larger photo »

-

Train Tracks

In April 1945, these tracks brought a convoy of Jews from Flossenbürg to the train station in Schwarzenfeld. See a larger photo »

-

The Train Station

The train from Flossenbürg arrived late on the night of April 18, before the station opened, and it limped into the yard early on April 19. A few hours later, American low-fliers opened fire, mistaking it for an enemy troop convoy. See a larger photo »

-

Scars of Time

Take one look at that old, red wound of a building and you can feel that terrible events happened here. In the yard outside this red brick warehouse, SS guards executed Jews wounded during the attack on the train station and prodded remaining captives to take their first steps on the Flossenbürg Death March. See a larger photo »

-

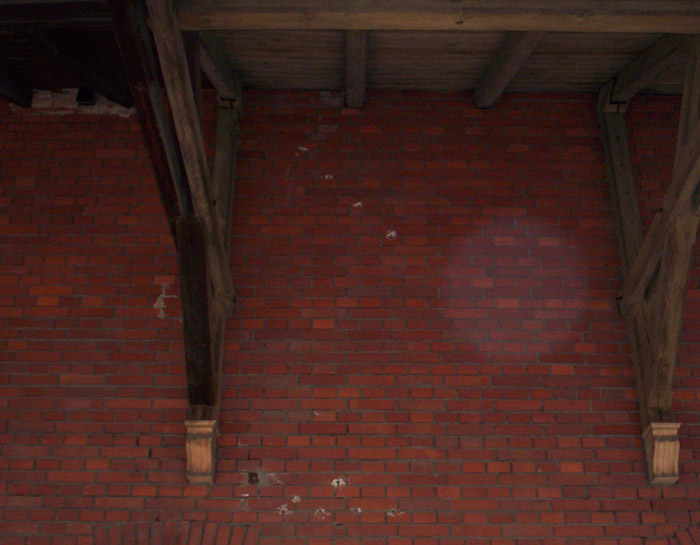

Bullet Holes?

The pocks in that red brick siding certainly look like they resulted from a strafing. See a larger photo »

-

Site of an Escape

Five prisoners managed to escape the train station massacre by crawling through the ground-level window of the warehouse. They managed to evade detection until American forces arrived four days later. See a larger photo »

-

The Mass Grave Site

In April 1945, this shady meadow was the site of horror beyond imagination. After the train station massacre, the victims were carried by wagon to this spot and hastily spattered with a coating of lime powder to prevent the spread of disease. On the morning of April 23, 1945, American infantry scouts discovered the mass grave. See a larger photo »

-

The Funeral Site

On the morning of April 25, 1945, five hundred Schwarzenfelders congregated here and attended the burial service for victims of the train station massacre. See a larger photo »

-

The Weight of the Past

There are places in this town that are heavy with memory. Keenly aware of the events that transpired here, we often felt that we were treading upon hallowed ground. See a larger photo »

-

Marker

In May of 1957, the bodies of the victims were disinterred and moved to a memorial cemetery in Flossenbürg. This granite plaque marks the original burial site. See a larger photo »